When John Mason moved on to Hillview as one of the first shortlife tenants, he did not think he would still be there some 40 years later.

After being burgled three times in one flat he ended up in another on the ground floor near one of the entrances. “It did not take long for me to realise just how vulnerable I was when I had to take a man to A&E after he’d been attacked in Argyle Walk,” he tells me, referring to the once seedy alleyway that flanks the north side of the estate.

Argyle Walk, which flanks the estate, and was once a no-go area, and a Hillview walkway before refurbishment

But as hundreds more shortlifers joined him, he found himself drawn into efforts to turn the crime-ridden slum into a thriving community and is still here to tell the tale.

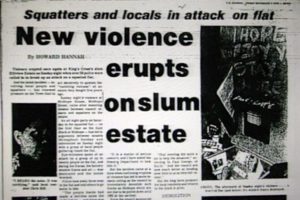

When John Mason moved onto the estate, Hillview was regularly making the headlines. From the Camden Journal, 1978

There was not much room for manoeuvre, anyway. “As a single man I had no chance of getting a council flat and the private rented sector had totally collapsed,” explains John, a retired researcher and social studies lecturer.

“The beauty of shortlife housing is that it created social stability by operating as a buffer zone between homelessness and secure housing,” he adds in a Lancashire accent seemingly unmodified by decades of London life. “So although there was a housing crisis, you simply didn’t see people sleeping rough like you do today. ”

John now lives in Midhope House, in a spacious one-bedroom flat that matches his scholarly looks with its many books and papers. His bedroom overlooks a leafy courtyard where armed gangs once fought for control of turf. “Years ago my students used to recoil in horror when I told them that I lived in King’s Cross, It was the sort of thing you normally kept quiet about, ” he laughs. “Now it’s gone from bleak to chic.”

He speaks with pride about the unique style of housing management that he and other residents were actively involved in establishing on the estate with the help of the Hillview Residents Association (HRA).

“As an experiment in co operative democracy its record was never perfect,” he admits. “But we ran the estate in a way that was sensitive to the needs of tenants and created a very tolerant and inclusive atmosphere.”

CHA chief Mick Sweeney (left, seated) with housing minister Nick Raynsford and Mayor Heather Johnson at regeneration unveiling in 2000. T-shirted tenants indicate that relations with CHA have got off to a bad start. Courtesy, J Mason

He contrasts this with the approach of One Housing Group, formerly Community Housing Association (CHA), which took over Hillview from the council in 1994.

“It inherited a very well run estate but from the beginning refused to recognise the HRA, for many years banning us from using the tenants hall it had just refurbished.” says John, adding firmly, “However, they cannot ignore us completely.”

There have been numerous clashes, not least over One Housing’s decision to let a number of flats at market rents, more than double the social housing equivalent. John shakes his head at the mention of it. Nevertheless, for him Hillview remains a monument to the ideals of the shortlife era, when community was everything.

“It is a success story, albeit with qualifications,” he states. “It is also real privilege to be able to live in central London just across the road from the British Library and at a rent I can afford.”

Story by Angela Cobbinah, photos reproduced with the kind permission of John Mason