It isn’t Somers Town

Father Philip Dyson grew up in the north of England, and moved to Somers Town in 1980. He spent 15 ½ years there, as the Vicar at St Mary’s Church. A community of “old Cockneys” inhabited the Somers Town that Father Philip remembers. There was no development around either of the stations then, the British Library was still a derelict goods yard to the west of St Pancras Station, and Granary Square was yet to be transformed into the glitzy hub of fashion and fountains that is has become since Central St Martins moved there in 2011.

His enthusiasm for the area, its history, and its people, is evident when I speak to him from his current parish in Penzance. Cornwall is stunning, he tells me, but it isn’t Somers Town. Father Philip eventually left London, St Mary’s Church, and the Church of England to boot, in 1995. He became a Catholic Priest, and moved to his current posting, in a diocese that stretches over 200 miles, and includes Poole to the north-east, and The Isles of Scilly to the south-west.

Father Philip was the Vicar at St Mary’s in 1985, when George Eugeniou from Theatro Technis (a Greek Cypriot theatre close by on Crowndale Road) approached him and asked if he would offer Sanctuary for a young Greek Cypriot couple – Vasilis and Katerina Nicola. Vasilis and Katerina had been living in London for nine years when they were served their deportation papers and told to leave the country. For more detail on the background and context of their ordeal, listen to George’s story.

The Church is for justice and peace

Faced with the situation at hand, and assuming that the couple would stay in the church for two to three weeks, Father Philip agreed to offer them sanctuary. Although contemporary English law offers no legal immunity from arrest to people sheltering in churches (as George discovered when researching the play that inspired the sanctuary), between the forth and seventeenth centuries, it did offer such protection. In the name of tradition, authorities are reluctant to this day to enter churches to arrest those that have been offered sanctuary within them.

Father Philip thought of the action as a “little protest”, against a legal system that was prepared to send innocent people back to a country where they were unsafe. When I ask him how it was that the sanctuary ended up lasting five months, he tells me, “We were holding out, playing for time with the authorities”. In the end, the sanctuary only ended when Katerina fell ill and the couple were forced to leave the church. They were ultimately returned to Cyprus, but were offered a safe haven in the Southern part of the island, which remained under Greek control.

Father Philip remembers the night that the couple arrived at the church. He and George – both small men – were faced with two immigration officers, both over 6ft tall, telling them to release the couple into their hands. Father Philip remembers calmly replying ‘no, that’s not what we’re going to do’.

Initially Katerina and Vasillis slept in the church hall. Father Philip was amazed by how supportive the local Cypriot community was – with young men coming to sleep at the church as extra protection for the couple. “They were an innocent couple, caught up in [the fall out] of this Turkish invasion, who lost everything. And no one was in sympathy with them, except for their community”. And beyond the local Cypriot community, Father Philip remembers, “The lovely Somers Town people were so supportive of the sanctuary”.

When I asked him what inspired his certainty that offering sanctuary was the right thing to do, he told me, “I felt this is a great injustice, and the church is on the side of justice and peace. Society talks about law and order, but the church works for justice and peace. There’s a big difference. I felt there was no justice for this couple, and without justice, there could be no peace”.

“Oh no Father! I never go there”

One of the things that stood out for Father Philip about Somers Town was how tight knit the area was. It wasn’t then the transient space that it is becoming as the likes of Google and YouTube become established neighbours. People born in the area didn’t move far, he tells me. And then to illustrate the point he takes me through a typical lifetime of a Somers Town resident. “People were born at home, many of them worked in the workhouse at the back of the Veterinary College, then, in the end, they were given a space in the boneyard at St Pancras Old Church”. He doesn’t specify the era that his imaginary resident was living in, but the site of St Pancras workhouse, was operational until the 20th Century, and is now home to St Pancras Hospital. According to the Office for National Statistics, home births in the UK became almost statistically insignificant between 1961 and 1971 in the UK (though they began to rise again after the late 1980s).

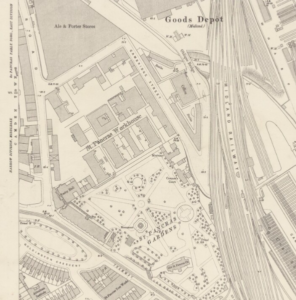

Ordnance Survey Maps, London, showing close-up of St Pancras Gardens and Workhouse (1893-1896) – Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland – Map images website

Even after the demise of the workhouse, this tendency not to travel far was still prevalent in Father Philip’s day: He remembers having a conversation with the careers leader at a local school in 1984 and discussing a job that he had managed to secure for two local lads, out in the west end, about a mile and a half from where they lived. “That’s much too far to travel to work!” they had replied.

He also remembers Flo, a parishioner, who, at the age of sixty, had lived in Somers Town her entire life. Father Philip had been leading a fundraising activity for a local good cause, and had asked his volunteers to meet over on the other side of Euston Road. “Oh no Father” Flo replied, “I never go there, I get lost”.

There was a real fear of the unknown; he explains to me, “people only felt safe in their own manor”. On the other hand, when it came to fighting, sticking around in a neighbourhood where people knew you wasn’t an option. The Somers Town lads, and the Kentish Town lads, Father Philip recalls, would meet in the middle, in Camden Town, for their punch-ups.

He chuckles at the thought. Then he tells me that he could talk all night about Somers Town, about “what went on, what could’a gone on, what might have gone on, what ought’a’ve gone on”. And then he excuses himself, and returns, I imagine, to attend to the spiritual needs of his Cornish parishioners.

Story by Polly Rodgers